There are quite a lot of flashlights in this house.

So, of course, I had to go and buy another one.

It only cost me ten bucks from this eBay seller. And it's possible that it's actually a genuine antique.

Which is a bit unusual, for an electrical device. Especially one that works.

The generally accepted definition of an antique is something at least a hundred years old, and flashlights that looked much like this one certainly were on sale a hundred years ago.

The first portable electric lamps appeared in the last few years of the nineteenth century. The first commercially successful one was the boxy Acme Electric Light, in 1896. But the easier-to-hold tubular flashlight was first sold commercially, by one Conrad Hubert's Ever Ready Company, in 1899.

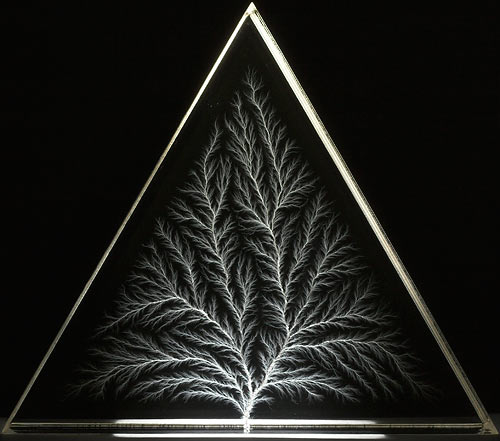

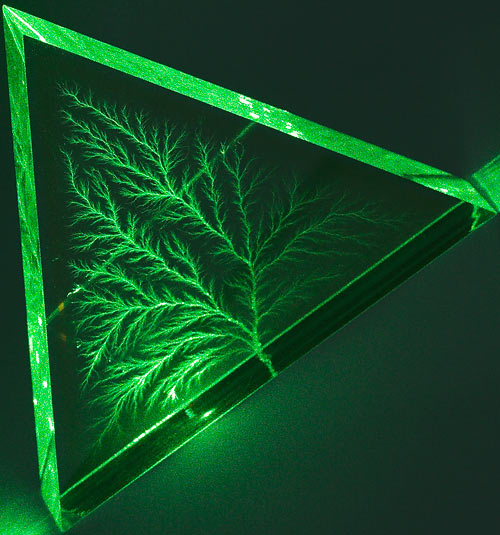

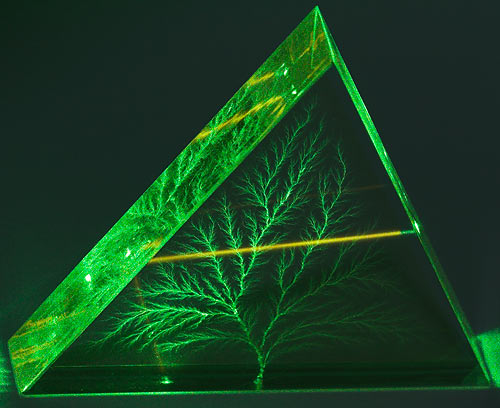

This light probably isn't nearly that old, but it's still got the thick "bullseye" glass lens that all tubular flashlights had for the first decade or so of their existence.

(If you ask me, "bullseye lens" should only be the term for the concentric-circles fresnel lens, as seen in lighthouses and stage spotlights. This kind of flashlight lens could more correctly be called a "dome". But "bullseye" seems to be the most common term. "Walleye lens" seems to be another term for the same thing.)

The bullseye lens was not a good design.

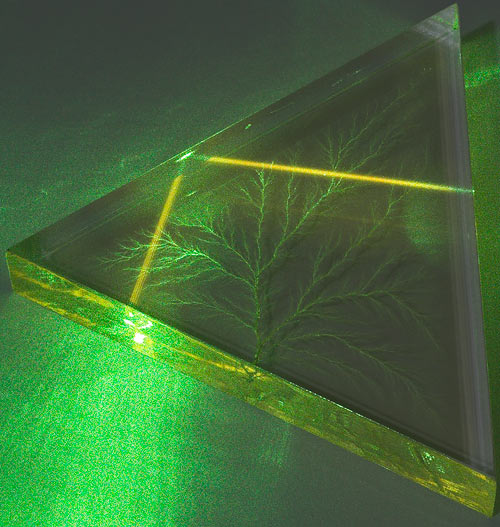

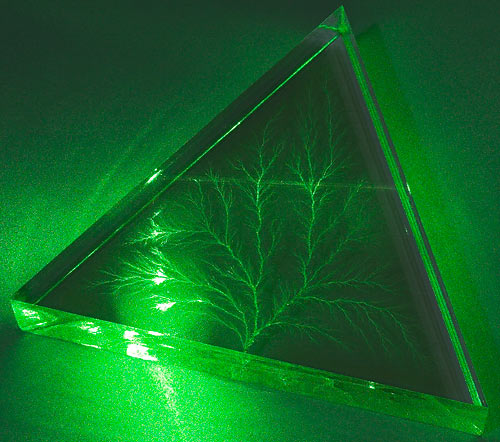

It's either planoconvex (flat on one side, convex on the other) or, as in this case, slightly concave on the inside and much more convex on the outside. Either way, the lens gives the flashlight a very broad beam.

The beam width is at least 60 degrees, for this light, and it has no central "hot spot" at all. It's quite unlike the output of the more usual kind of incandescent-bulb flashlight, with a thin flat lens on the front and a relatively large reflector around the bulb.

A super-wide beam is great for seeing where you're going, but useless for seeing anything at a distance. This was quite disastrous for flashlights a hundred years ago, because they weren't very bright at the best of times.

This light was probably made to take a tungsten-filament bulb, but those weren't very efficient until the coiled-coil filament was introduced in 1936. Earlier still were the even dimmer, more fragile and rather inconsistent carbon-filament bulbs. And the old batteries had lousy capacity, and lousy current delivery, too.

So overall, old flashlights needed all the light-concentrating help they could get.

But instead, everything that wasn't big and boxy like the Acme Electric Light got a fish-eye lens.

It's been postulated that the bullseye lens was so popular for so long because consumers thought it concentrated, rather than dispersed, the light from the bulb. At a glance, you might think that - look at the bulb through the lens and it appears huge, just as it would if it were in the middle of a big reflector.

But with a bullseye lens, the bulb appears huge from every angle, because light's being thrown everywhere.

I suppose people were accustomed to wide-angle illumination from fuel-burning lanterns. The flame from a lamp with a wick is too large a light source to be effectively concentrated by a reflector of readily carryable size, and there are further problems with just getting a reflector in there, next to a hot and possibly smoky naked flame.

Directional lamps did have reflectors - miners' acetylene carbide lamps are an excellent, and surprisingly practical, example - but they still threw a very wide beam.

(Which, in the case of the carbide lamp, was quite respectably bright even by modern standards. A small "helmet" carbide lamp can easily throw as much light as a five-watt incandescent bulb, and it could do it for several hours. Five watts for five hours is 25 watt-hours; that's about the same amount of energy as you'd get from two modern C alkalines. Carbide lamps are little more than a hundred years old; they were quite revolutionary in their day, and far superior in light output and safety to kerosene or other oil lamps. Carbide lamps were still perfectly capable of burning your house down, though; you could only do that with the new-fangled electric lights if you really tried.)

Bullseye-lens flashlights hung around long after the common availability of modern large-reflector, flat-lens lights - note the Prohibition-era hip flask in the shape of a bullseye flashlight here. So it's quite possible my little light is only about seventy years old. That's still pretty impressive for a device that's still useful today, though.

A nice one of these lights would be an Eveready Daylo, or something. This one's a brandless version with no decoration, cheaply made from sheet metal, so it's probably worth nothing to a collector.

Like other lights of this size and vintage, this flashlight wants a weird battery - a 2R10 "Duplex" or "2B". That's a three-volt, two-cell battery that's apparently about 75 by 22 millimetres in size, and still available today, if you're really dedicated and/or willing to take apart another battery. The 2R10's dimensions make it quite magnificently incompatible with every common battery today.

A 75mm-long battery must have been a pretty tight fit in this light, though, because it turns out that a modern 18650-size (18mm wide, 65mm long) lithium cell fits very nicely, especially if I screwed the bulb all the way in.

But, to do that, I did need a bulb.

The bulbs this old light uses, fortunately, are quite standard. They're the same miniature Edison screw (MES) type that survive in small cheap lights today. (Though no doubt not for much longer, since LEDs are now clearly superior.)

An odd flattened-bulb vintage MES lamp came with the flashlight, but of course did not work any more. I had a cheap push-light doodad sitting around waiting to have some RGB LEDs put in it, so I harvested the bulb from that. It was meant to run from four 1.5V cells and so should have been reasonably bright from the roughly four volts of the 18650 cell, but it was actually quite dim, and died after not many minutes of use.

So I got an Eveready MES bulb for "5D" flashlights, rated at 0.3 amps at 6.2 volts, and tried that. The flashlight's much brighter now, though it's probably running its bulb at rather less than half of its 1.9 watt rating.

The low voltage makes the flashlight's output very yellow, which I find quite pleasing in this age of blue-white LED flashlights. The light colour's probably quite similar in hue to the light from its original lamp, but brighter. It's perfectly usable as a night-time seeing-where-you're-going light.

I wasn't expecting it to be this easy to make this light work. I thought I'd have to hack some LEDs into it, or something. But it turned out to be easy to fix, in a more authentic manner.

It's been foggy, lately, and now it's getting dark. I believe I may procure myself a Webley revolver, and sally forth with my newly purchased "hand-torch" to investigate the night-cult that drunkard spoke of in the inn, before his fellows silenced him so brutally.

I'm told that a torch whose light is feeble may be a blessing.

There are things which are best not clearly seen.

Buying one

The eBay dealer I bought my bullseye-lensed flashlight from now seems to be dormant, but similar items show up on eBay pretty frequently. They can be a pain to find, though.

This search right here finds anything that could be a real old bullseye flashlight and filters out a lot of useless results, but it's not quite the same as the actual search I've got saved and sending me e-mails just in case a cheap light even prettier than the one I've got shows up. That's not because my search is a trade secret, but because there's a limit to the length of the search string you can link to via the eBay affiliate thing. The full search string, for your cutting and pasting pleasure, is:

(old,vintage,antique) (torch,flashlight) -paisley -"pipe lighter" -"torch green lighter" -"green flame" -"torch lighter" -blow -heat -kero -kerosene -kerosine -projector -patent -bulbs -pin -pins -bearers -guitar -spirit -blowtorch -cutting -bead -"ornamental lighter" -"ornamental gun"

To throw an even wider net, it's easy to search for flashlights in the eBay "collectibles" category (here on eBay Australia and here on eBay UK, both with the added search term "torch" to find Commonwealth-usage listings and clutter the results with ancient rusty dangerous blowtorches). But the results in that category aren't very good; you get a lot of brand-new LED lights and plastic crap from the Seventies. People selling bullseye-lensed lights unfortunately seldom describe them with a handy searchable word like "bullseye" or "dome", so you pretty much just have to scan the thumbnail pictures until you find one.

Do the same search in the "antiques" category (here on eBay Australia, here on eBay UK; I've left "torch" off the search string this time to avoid zillions of hits for tiki torches and candelabras) and and you'll find a lot more genuinely old flashlights. "Antique" bullseye-lens lights that aren't just a pile of rust with a lump of scratched glass in the middle, though, are generally pretty expensive.

Some of them are very beautiful, though. The "bicycle light" type that's a wooden box with a handle on top and a lens on the side is particularly appealing, especially after a dab of wood polish. Box-lights usually have plenty of room inside for modern batteries and lamps, too, so you probably won't even need to disturb the dreams of the world's flashlight collectors by destroying the old fittings in order to shoehorn in a pink LED and lithium battery.