There are people on eBay selling "liquid metal bullion".

They don't like to tell you exactly what metal this alleged "bullion" is, except they always swear it doesn't have any mercury in it.

They generally say it's solid at room temperature, but will melt from the heat of your hands.

Those of us with a mild recreational interest in the periodic table will draw a rapid conclusion if given the characteristics "metal, melts at body-heat temperatures, doesn't explode on contact with moisture...

...and non-toxic."

That'd have to be gallium, right?

Wrong. I bought some, and it's nothing like the gallium I already own.

I didn't know what the hell the "liquid bullion" was. Not, at least, until I played around with it for a while.

There seems to be some sort of tradition in the hobbyist low-melting-point-alloy business of casting your little ingots in unorthodox moulds. The mould is usually something that clearly indicates that the metal was liquid at temperatures low enough that to not instantly destroy a chocolate-box tray, silicone ice-cube tray, or similarly non-refractory mould material.

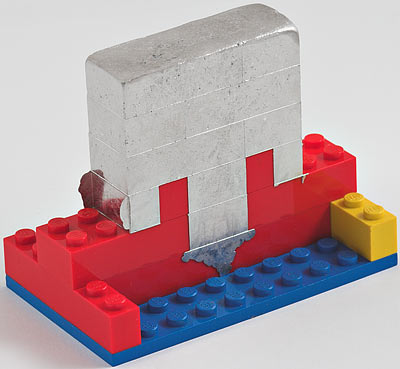

I cast my own Wood's metal in a Lego mould.

You could craftily fake this by casting wax in a chocolate tray, then using that form to make a sand mould, or something, but I don't know of any such scandals in the retail weird-metal market.

All of the low-melting-point alloys exist because of the odd fact that mixtures of chemicals can have a lower melting point than any of the ingredients.

On the face of it, this doesn't make sense. I mean, the universe should be nice and sensible and line up with the way ancient philosophers hoped it worked, from tiny billiard-ball atoms all the way up to clockwork galaxies. Then, the melting point of an alloy would be the melting point of its constituents, weighted by what proportion of the alloy each constituent took up. So for Wood's metal, for instance, you'd have:

50% bismuth, melting point 271.5°C

26.7% lead, melting point 327.46°C

13.3% tin, melting point 231.93°C

10% cadmium, melting point 321.07°C

Weighting each of those by the fraction they take up gives 135.8, 87.4, 30.8 and 32.1; add those up to get your naïve simple mathematical logical melting point and you get 286.1°C.

The melting point of Wood's metal is actually only about 70°C. Stuff like this is why metallurgy was much more art than science for a long, long time.

(In case you're wondering, which you probably aren't but I was, for these kinds of calculations it's safe to use Fahrenheit, Celsius or Kelvin temperature scales. The arbitrary zero points of Fahrenheit and Celsius don't screw it up. Beware anybody who tries to tell you that a 30°C day is "twice as hot" as a 15°C day, though, because that's so dumb as to possibly be not even wrong. 15°C is 59°F, for instance; making 59°F "twice as hot" gives you 118°F, which is 47.8°C. Kelvin starts at absolute zero, so it's the only scale in which you could actually fairly say one temperature is twice another, though I'm still not sure how useful such an observation could be. Starting at -273.15°C makes "doubling" room temperature in Kelvin rather dramatic, though; 15°C is 288.15 Kelvin, double that is 576.3 K, which is 302.85°C.)

Many alloys don't have this oddly low melting point. Brass, for instance, has a melting point from about 900 to about 940°C depending on its formulation; it's composed of copper (melting point 1085°C) and zinc (melting point 420°C). The melting point of brass is higher than you'd expect from naïve proportion calculations.

But the most common low-melting-point alloy is ordinary tin-lead solder, which exhibits the melting-point-reduction effect. Tin melts at 232°C, lead melts at 327°C, but if you mix 63% tin with 37% lead you get an alloy that melts at only 183°C.

And so, back to my "liquid bullion" ingot, which I bought on eBay Australia for $AU19.01 delivered after watching several people buy their own for prices that exceeded my modest snipe.

It was quite small. Only about four centimetres in length...

...and it weighed more than fifty grams.

That made it dense enough that, despite the seller's claims of non-toxicity, I treated it as if it were made of solid cadmium until I could figure out the thing's composition for myself.

(The seller was this guy - possibly NSFW! - who is now out of the "liquid bullion" business, having found the whole thing to be "nothing but a headache". That "NSFW" is there because after he got out of the liquid bullion business, he sold several pornographic coins. I am not making this up. As I write this he's only selling a sofa, but I'm sure he'll offer the Internet flea market some more eyebrow-raising products in the near future.)

The listing for my "bullion" ingot gave no hints regarding its makeup, but I bought it anyway, partly because low-melting-point metals interest me. I also figured that "liquid metal bullion" might be just as entertaining as "copper bullion", with which I had a lot of fun a few years ago.

(Tl;dr: Base metals sold by the troy ounce may be a fun novelty, but are not a good investment.)

Copper-bullion sellers are still rampant on eBay, but this liquid-metal schtick is new, and extraordinary.

It is, you see, mystery bullion! An unknown metal! Usually billed as very rare and valuable and desirable, whatever it is, but available to you today for amazing prices!!1!

I saved the listing from which I bought my little ingot. I won't upload the whole page-copy here, though, because malware-detection services tend to flip out, with some justification, if they find what looks like an eBay listing on some site other than eBay.

Here's what the listing said, though, with only the eBay trimmings and images removed.

Children, avert your eyes! Just reading this may delete more than a year of science education from your brain, and make you noticeably less intelligent than you were before!

999 Pure Liquid Metal Bullion INGOT 99c A GRAM 52.6 Gram Not 1oz Silver bar Coin

This Metal Alloy IS NOT MERCURY AND DOSE NOT CONTAIN ANY MERCURY.

It is PURE HIGH GRADE

LIQUID METAL BULLION

You will receive 1 ONE

Ingot as pictured which weighs 52.6 GRAMS IN TOTAL. Size is (1 & 3/4" long) (1" Wide) (1/4" High)

"BULK INGOT ORDERS WELCOMED"

"MELT AND MOLD INTO WHAT EVER SHAPE YOU LIKE"

FOLLOW THIS LINK TO SEE HOW

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=foQhHfsyPIc

Purchase as many as

you like. You will only pay the quoted postage cost as I will cover any EXTRA

POSTAGE COSTS!

This metal is

considered bullion as it is pure rare

earth.

It melts at the low

temperature of less than 30 degrees, will even melt in your hand if held long

enough.

IT IS NON TOXIC

AND NON HAZARDOUS TO HANDLE

Spot Price is

increasing at a rapid rate with the demand of this

Pure Liquid Metal

Bullion

Only 99 cents per

gram and one off low postage cost of $3.00

There's... I mean...

Look, I'm not even going to start with that description. It's the sort of scientific word-salad more often seen in explanations of crackpot cancer cures.

Oh, OK, just one thing: "Rare earths", and metals which are precious for their rarity, are not the same thing, no matter what certain eBay sellers think.

The elements known as "rare earths are actually quite common; the only "rare" thing about them is their concentration in any given load of ore, meaning you need to dig up a lot of the planet to get a little bit of rare-earth element. And then it's difficult to separate the different rare earths from each other, because several of them have very similar chemical properties.

Rare-earth elements are today used to make neodymium-iron-boron magnets, hence the term "rare-earth magnet". Modern lighter "flints" are made from a very sparky, pyrophoric...

...and somewhat excitable...

...alloy of different rare earths, plus a few other things and iron for strength.

Rare-earth magnets and lighter flints are not very expensive per gram, though, because they contain no precious metals. For a few bucks you can now buy a ferrocerium stick intended for use as an emergency fire-lighter - just scrape it with a knife blade, file or similar item to create a shower of sparks.

(There are fancy versions of these things with built-in scrapers, but a simple bare ferrocerium rod is almost as good. You can get a little one with a handle, perhaps a stick of magnesium too for use as high-temperature tinder, and a bit of hacksaw blade for scraping and spark-striking, for about a dollar delivered. A chunkier bare ferrocerium rod will only set you back a few bucks from a dealer who doesn't quite know the difference between magnesium and ferrocerium, and may theoretically save your life one day. It will definitely provide you with considerable entertainment and some tiny holes burned in whatever happens to be near you when you play with it.)

The YouTube link in the above exercise in eBay creative writing goes to this video, from the brain-polluting "HouseholdHacker". That dude used to make ridiculous practical-joke "how-to" videos, which on the one hand encouraged a lot of adults to do entertainingly silly things, but on the other hand probably turned some kids off science. Which took that guy right the hell off my Christmas-card list.

Now, though, HouseholdHacker seems to be producing serious videos. The one linked to by the liquid-bullion guy isn't what you'd call packed with educational information, but the only actual inaccuracy I noted in it was incorrect rounding so the melting point of gallium was 0.1°F off. That is not exactly a capital crime.

But I still think that you're going to transition from "joke videos to get people to do stupid things" to "actually telling the truth", you shouldn't keep your old name. Mixing the two is completely uncool, man.

(Oh, and while I'm on this subject, see also my favourite example of this latter crime. Good ol' Kip deleted all of his highly remunerative Metacafe videos at some point after he reinvented himself as the video face of Make magazine, thereby ensuring that I stopped watching any of their videos. I think Make came to their senses and quietly fired him after a year or three; their videos are much better now, and they've recently started an interesting new series.)

If you want a video about low-melting-point alloys that's not from a professional bullshit artist, you could do a lot worse than turn to "Brainiac75":

Oh, and if you want a good video about gallium alone, then you obviously need to turn to actual scientists...

...and their magnificent example of an actual scientist who looks like a mad one from a horror movie.

Aaaaanyway, anybody who hasn't yet died of old age reading this page may remember that the question was... what is this "liquid bullion" stuff?

While I was sniping auctions, little fifty-gram ingots like mine kept selling for twenty-five Australian dollars or more. That's a good price for fifty grams of gallium, but it's not a good one for a similar amount of toxic low-melting-point alloy. Small amounts of anything cost more per gram, but you don't have to buy a huge amount to pay a lot less. Brainiac75 above said he paid only ten Euro cents per gram for some of the lower-melting-point alloys in his videos.

(The very lowest-melting-point alloys in Brainiac75's video are alarming concoctions like an amalgam of periodic-table neighbours mercury and thallium. That is not ten cents per gram, but it stays liquid down to -60°C. Cesium-potassium-sodium makes it down to -78°C without solidifying, but it also explodes on contact with water.)

For my first attempt at identifying the metal, I contacted the seller thusly, batting my eyelids innocently:

I've received my little ingot, and now I find myself wondering what it's actually made of. Your listing doesn't mention this, other than to say that it contains no mercury. What actually IS this alloy?

I'd also be interested to learn where to look up the "spot price" you mention in the listing. (Which again, of course, requires me to know what alloy this actually is.)

Thanks!

While I waited for him to reply, I measured the little ingot's density.

Accurately calculating the density of a small object is tricky. Getting a vague ballpark figure isn't hard, especially if the object is roughly a rectangular prism, as this one was. Just measure the edges, fudge any bevelled edges into a sensible-looking in-between number, and then multiply the numbers. Doing that with the little ingot gave me a volume of about 5.6 cubic centimetres. Since it was bang on its advertised mass of 52.6 grams, this gave me a density of about 9.4 grams per cubic centimetres.

The density of solid gallium is only 5.91 grams per cc, so clearly this wasn't gallium.

(Gallium is also one of those odd materials that expands when it freezes; liquid gallium's density at its melting point of 29.8°C is about 6.1 grams per cc.)

My faithful triple-beam laboratory balance gives me quite accurate weight numbers, but I wanted a more accurate volume than fudged dimension-multiplication could offer.

When a metal has a low melting point you can, of course, just melt it and pour it into a graduated cylinder to measure its volume. But gallium, if there was any of it in this alloy, tends to "wet" a wide variety of other substances. So, presuming there was gallium or something that behaves like it in this alloy, getting all of it out of a narrow graduated cylinder again could be difficult.

Another way to measure volume is by filling a graduated container with water or oil or whatever else is compatible with the object whose volume you want to measure, and then dropping the object into it and seeing how far the water level rises. This often doesn't work any better than just measuring the edges, though. It's a good quick strategy for extremely irregular objects - figuring out this technique is what is suppose to have sent Archimedes running naked down the street shouting "Eureka!" - but I've tried it several times with different items, and every time I got miserably inaccurate results.

There's a much better way of measuring object volume by immersion, though. You just need to add a precision scale to your apparatus. Pretty-well-calibrated 0.1-gram-resolution digital scales are now commodity items, and my abovementioned lab balance will do the job nicely.

What you do is, you put some water - or, again, a different liquid if water is incompatible with the object you're measuring - in a vessel deep and wide enough to completely submerge the item whose volume you're measuring, without the object having to touch the bottom.

You then weigh the vessel and the water, or just press the zero-out "tare" button on your digital scale.

Now, you immerse the item you want to measure in the water. If it's less dense than water you have to push it down into the water until it's fully submerged, but it's probably more dense than water, in which case you can just suspend it rather than push it in.

The important part is that the object must be immersed, but not resting on the bottom of the container. This is because what you're measuring is the increase in weight of the container, not the rise in level of the liquid in it.

Whatever you suspend your object with should have as close to zero volume as you can manage. I used some kapton tape, partly because it is narrow and extremely thin yet has good adhesive, but mainly because it is unquestionably the scienciest of all of the more than two dozen kinds of tape I have to hand.

("Florists' crepe-paper tape?" Got that. "Colourful metallic tape less than a millimetre wide meant for decorating fingernails?" Yup. "Copper and aluminium foil tape?" Of course. "Self-amalgamating?" Which kind would you like, the old rubbery type or the new silicone stuff? "Gaff?" Multiple colours. "Foam draught-excluding door-seal tape?" Please. "Bendable-fridge-magnet tape?" Yes sir. PTFE thread-sealing tape? Naturally. "Unstretchable fibre-reinforced tape?" Ashamed to say I have only glass-reinforced, must get the aramid kind too. "Velcro tape and liquid tape?" Possibly the first and definitely the second doesn't really qualify as tape, but I've got 'em both anyway. And you can buy off-brand probably-kapton polyimide tape all over the place these days; it's generally just called "high temperature tape".)

Again, if you're measuring the volume of a ping-pong ball or something by the immersion method then you'll have to push it down into the water, but that'll still work. You could push it in with three needles mounted on some gantry over the scale, for instance.

Anyway, you suspend or shove the thing you're measuring into the water, suspending or shoving as little other stuff in there as possible, and the vessel will then become heavier by the mass of the liquid the object has displaced. Water weighs one gram per cubic centimetre at one gravity, so presuming you're using water and don't need numerous decimal points of accuracy, each gram of weight gained equals one cubic centimetre of object volume.

If you're now having some kind of "common sense" brain-spasm, wondering why a ping-pong ball shoved into a glass of water should make that glass as much heavier as would an identically-sized sphere of tungsten suspended in it, you may find this PDF soothing.

The initial mass of my glass plus water was 436 grams even; dangling the "bullion" ingot in it raised that to 441.5 grams, for a volume of 5.5 cubic centimetres.

This made me pleased about my original guesstimate of 5.6 cubic centimetres, though slightly less pleased about the time I'd spent bent over a laboratory scale to get a scarcely-different number. It's a bit like that story about how the Great Trigonometric Survey painstakingly measured the height of Mount Everest and came up with exactly 29,000 feet. That's exactly how tall everybody had always said the mountain was anyway, so, the story goes, they added another two feet to prevent people thinking they'd actually just gone to ground in a club in Calcutta and spent their time inventing snooker and the gin and tonic.

Anyway, 5.5 cubic centimetres and 52.6 grams gave me a density of 9.56 grams per cubic centimetre.

I now had a reply from the seller regarding what he reckoned I'd actually bought. He said:

Hi, the metal is frenchs metal type3 or gallium, both the same.

Hmm.

He was receptive to my then pointing out that "French's metal" and gallium are very much not the same, the latter being non-toxic and the former containing both lead and cadmium. It was at this point that he told me he wasn't selling this stuff any more on account of its headacheyness, which is I suppose one way of describing what happens when you sell poisonous heavy metals, both lead and rather more scary cadmium, as "non toxic and non hazardous to handle".

"French's metal" is an unusual term for an unpopular substance. It's easy to find people selling Wood's metal, which is bismuth, lead, tin and cadmium, and melts around 70°C. Rose's metal is also pretty commonplace; it's just bismuth, lead and tin, so not as poisonous as Wood's metal, and melts just below the boiling point of water.

French's metal winds the melting point down to only about 41.5°C by adding indium to the Wood's-metal mix. There are some further variants that melt even lower thanks to the presence of thallium as well; if this stuff really melted in your hand, I strongly suspect it'd have to be one of the thallium alloys.

Which would be bad. Especially if you were melting it in your hand.

There are very good reasons to have as little thallium in your life as possible. Cadmium is something in the order of ten times as toxic as lead, but you can at least touch the stuff with your bare hands without appreciable danger, provided you wash your hands thoroughly afterwards.

Metallic thallium can pass through the skin, though, and is much more toxic than cadmium. Exact comparisons are difficult, because human thallium exposure is usually via one of its several useful-yet-toxic compounds, rather than the pure metal. But thallium is probably tens, if not hundreds, of times as toxic as cadmium. See this PDF from the US EPA, for instance, and compare with MSDSes (previously) for cadmium, like this one or this PDF one.

You really, really don't want to get any thallium on you.

(One of the symptoms of thallium poisoning is that your hair falls out. Needless to say, this means thallium sulfate used to be used as a depilatory, not that long ago. See also the use of lead and mercury compounds for skin whitening. Thallium is also still used in some countries to poison rats, ants and troublesome spouses.)

Fortunately, most people don't need a fusible alloy that melts at as low a temperature as bismuth-lead-tin-cadmium-indium, and fewer people still need the alloys with thallium as well. Presumably, because of this relative unpopularity, "French's metal" and its relatives are often not called that, and just stuck on page 137 of the specialist-alloys catalogue with no name beside their ingredients and melting point.

On with the investigation, then. What actually is the melting point of this stuff?

If it were pure gallium then it would indeed melt in your hand, provided the ambient temperature was high enough; gallium melts at 30°C (86°F). It's too dense to be pure gallium, though, so if it melts at blood temperature then it's probably terrifyingly toxic.

"French's metal" formulations - without thallium - are frequently quoted as melting at 117°F, which is 47.2°C, way higher than any survivable body temperature. Similar alloys with added thallium are quoted as low as 105°F, which is 40.6°C and still not "body temperature" unless you're quite gravely ill. Measuring the melting point can therefore help me decide whether it's moderately-nasty French's metal or some handle-with-gloves thallium alloy.

I've got a high-accuracy digital probe thermometer, from back in the day when I reviewed incredible quantities of CPU coolers. (It's tempting to simplify the setup by just pointing one of today's inexpensive non-contact infra-red thermometers at whatever you're heating, but in this case that wouldn't work.)

So I set up the sort of advanced experimental apparatus for which I am so justly renowned...

...with the metal ingot again suspended in water, but this time inside a resealable storage bag, of the type generically referred to as, but in this case not actually a, Ziploc.

The bag insulated the metal from the water, of course, and my temperature probe was in the water, not inside the bag to get all probably-cadmium-ed up. So I needed to be a bit crafty to get a useful melting-point number.

What we're interested here is how low the temperature the metal melts at is, not how high it is, if you get my meaning. So I ran the water temperature up to 50°C (122°F), at first. Then I turned the heat off and snapped the above picture of the setup, while the metal got around to melting.

After taking this photo, I hung the melted metal in its bag back in the water, and allowed the water to cool.

As the water temperature fell through the low forties Celsius, the metal started solidifying again. Crystals started forming in the liquid, so at first the metal in the bag felt like a dense liquid with a little sand in it, then more and more like unusually heavy wet sand, until finally it solidified entirely.

I think this might mean this alloy is non-eutectic, with no clear melting point because different components melt at different temperatures. It could also just be the normal way a cooling metal will crystallise if you keep poking at it and examining its texture, though - the "liquidus temperature" is defined as the temperature at which solid crystals can coexist with melted material. I'm not sure.

The metal was wholly solid again when the water temperature was 40°C (104°F). Taking the bag's insulation effect into account, that told me the melting point was above 40°C and below 50°C, so the "melts in your hand" claim was clearly disproven, but I didn't yet have much idea exactly which alloy I was looking at.

I then ran the temperature slowly back up again, and the metal was re-melting, with the same sandy-liquid feel, by the time the water was back up to 47°C. But, notably, not when the water was only at 42 or 43°C, which would indicate a scary thallium alloy.

And then a pinhole opened in the corner of the bag and tiny droplets started escaping, and I terminated the experiment before I got heavy metals all over the kitchen again.

(Perhaps a genuine Ziploc® Brand bag would have been tougher. Squishing a gritty liquid with 83% the density of lead around in a the pointy corner of a polyethylene plastic intended to contain only food would probably cause any such bag to spring a leak, though.)

I could have re-bagged the metal and kept refining my temperature range, but what I'd done so far makes me confident that the melting point is somewhere in the 42-to-47-degree-C range, and probably the upper portion of that range. So I'm about 95% sure that this is indeed some kind of French's metal alloy containing lead and cadmium, but not deadly thallium.

Conclusion

If you want a relatively inexpensive fusible alloy to play with, go for Field's metal. It melts at about 62°C (144°F), and it contains only bismuth, indium and tin, so genuinely is non-toxic. Bismuth and indium are a bit expensive, which means Field's metal is too, but you could cast a teething ring out of it and probably not harm the baby.

Describing any of these low-melting-point fusible alloys as "bullion", though, is if anything even sillier than doing the same for copper. They're not worth enough per kilo to be an investment item, and most of them contain lead, cadmium and/or even thallium, which makes them less "valuable heirloom" and more "toxic waste".

Here, along with one helpful wubble, is where my own "liquid bullion" ended up. I've left it in the triangular shape the corner of the plastic bag gave it, along with the little spherical droplets that escaped into the saucepan. It's quite pretty, covered with tiny sparkling crystal surfaces; cooling it slower might have made bigger crystals, though nothing that could compete with bismuth.

To the right of the "bullion" lump is my sample of gallium, which is currently solid. Gallium is one of those substances that'll stay liquid below its freezing point if nothing serves as a nucleation point to start it crystallising. (The same thing can happen with water and various beverages in smooth plastic or glass containers).

Gallium sticks to almost everything, though, so if you slosh it around in the bottom of a container it'll make a silvery mirror out of whatever parts of the container-sides it touches. Once it finally decides to solidify - which, for my gallium at least, can take weeks - you can flick the flexible sides of the container to break the thin gallium coating off them. The result is what you see in the above picture - uneven coverage of the sides with thin plating I didn't manage to dislodge, and random dislodged flakes of gallium sitting on top of the solid layer in the bottom of the container.

(I rather like these little PET bottles, by the way. My gallium came from the Amazon seller in a tough grey translucent container that doesn't show it off nearly as well as this new one. Five of these eighty-millilitre containers, about 8cm high and 4.5cm wide, only cost me $AU3.88 delivered on eBay. They seem to be a couple of bucks more expensive now. UPDATE: But because they're standard PET bottles blown to shape from a preform, they shrink if you put them in boiling water! I think I can re-liquefy my gallium in one of these bottles, but now I've got one funny-looking one from pouring too-hot water on it.)

As I write this, the spot price of silver is less than $US20 per troy ounce; precious metals in general have taken a dive in the last few months. The spot price for gallium is at the moment maybe $US500 per kilogram, and one kilogram is 32.15 troy ounces. So gallium is something like $US15.55 per troy ounce, right up there with silver.

There is, just as with copper, no real liquid market (pun not intended) for small quantities of high-purity gallium. But the value of the stuff is sufficient that if you manage to buy it by the kilo at close to the bulk spot price, it really could qualify as an investment.

If you buy fifty grams of gallium in a little bottle from that Amazon dealer then you'll be paying a large markup on the bulk price, as is normal for metals other than the generally-accepted "precious" ones sold at retail in ounce quantities. It's also possible to quickly turn gold, silver or platinum into cash, if you suddenly need to. In a similar situation with gallium you'd have a hard time finding people who even know what it is, much less people who'll buy it from you at a fair price, in a hurry.

On the other hand, gallium's value is closely pegged to its real usefulness in the world. Gold, silver, platinum and palladium all have real-world uses, but their value is far higher than those uses justify. A large slice of the precious-metals market is people buying the stuff as an investment or just a store of value, perhaps as an alternative to a savings account in their shaky local currency. (India, in particular, has a strong tradition of storing household money in gold.)

Precious metals have never been a good long-term investment in the modern world, but they're portable and fungible, and that counts for a lot, even if you accept that you could make more money with index funds, bonds, or often even crappy-yield savings accounts.

Nobody's casting gallium ingots and keeping them in Fort Knox, though. Which is just as well, because the stuff would totally pull a Cryptonomicon if you turned the heating up too far.

A bottle of sloshy liquid non-toxic gallium is a lot more fun than a similar amount of similarly-valuable but much-easier-to-sell silver, though. I think that's a fair trade.

But don't buy weird "bullion" of any kind from eBay dealers, especially ones that say their product is non-toxic but aren't actually sure what it is. And if you are an eBay dealer selling weird "bullion", for pity's sake figure out what it is that you're selling, lest you be the next schmuck to put a "safe for kiddies!" sticker on a lump of cadmium. Or worse.

11 July 2013 at 3:06 am

"Gallium is also one of those odd materials that shrinks when it freezes"

That makes it an odd material? I thought nearly everything does, and water is the odd one out.

I will admit that water is fairly common.

11 July 2013 at 1:11 pm

Brain fart - it EXPANDS when it freezes, like water, which is why the liquid density is higher than the solid density.

Fixed now - thanks!

12 July 2013 at 4:55 am

A fascinating read and good way to pass a few hours of insomnia. Of course trying to sleep again with that volume by weight experiment going around in my head wasn't at all easy.

13 July 2013 at 2:14 am

{USAian aerospace}

Rankine, of course, is also a safe and useful absolute temperature scale, being to Fahrenheit as Kelvin is to Celsius. The conversion is 459.something degrees.

Note that it is proper to use "degrees Rankine", whereas "degrees Kelvin" is certainly improper.

{/USAian aerospace}

13 July 2013 at 1:31 pm

I don't get how hanging an object in the water gives you its vol....Wait, buoyancy of an object equals the weight of displaced water so the upwards force is equal to a downward force on the container. Just like if it was floating...So simple. :)

14 July 2013 at 12:42 pm

Great article. There is an even quicker way to do the density measurement, starting with a tared container of liquid: take the reading while the object being measured is suspended, then drop the object and take a second reading (which is its mass). Divide the second number by the first and multiply the result by the liquid density. Quick and as accurate as your weighing device. When using water I'd add a drop of detergent to prevent bubbles attaching.

If your thermometer has a recordable output you could plot the cooling curve vs time, which gives more information; the curve plateaus at the freezing point.

If you had the patience for it, separating the first crystals formed when cooling and testing their melting point might help identify one component metal. You can do this until you reach a eutectic mixture; then you need to look up its melting point to identify it.

18 July 2013 at 12:24 am

[this is a response to the "seeing past normal" as there doesn't seem to be anywhere there to respond.]

If you want to see prediction done right, try Expanded Universe by Robert Heinlein. Inside is an article called "where to" which is (I think, it might be before that) an article originally published in 1950 that gives predictions of life in 2000. It was then updated in 1960? and 1980. Some of the predictions were iffy, a few were way to cautions (completed before 1960) but they seemed mostly right and RAH was grudgingly insisting that communism would fall before 2000 (he died in 1987). Other predictions of note:

Traditional marriage is unlikely to survive/remain its exclusivity. Actually, RAH had various forms of group marriage in mind, but it seems that such changes are happening.

"There is a device that will change life as much as the car, but we don't know what it is, unless it is the computer chip". Weak. Moore's law was published in 1969, it should have been obvious in 1980. It *hadn't* begun to change the world yet, so I'll give him that.

Another big point was showing that the enormous explosion in data without any better way to use it. His stories included "encyclopiac synthesists", but he pointed out that computer scientists were doing more to advance this idea. I can only assume that had he been alive, he would have invested in google early.