A few times a year, all the gadget blogs get excited about some new lighter-than-air vehicle. Sometimes it's a little one for the determined hobbyist, a big one for specialised cargo, or a huge one that's never even going to exist.

And then there are the modern Goodyear-Blimp tiddlers that're shamelessly described as "Zeppelins", despite only being a third - often less than a quarter - of the length of the proper ones.

I mean, look at the "Zeppelin NT". It's 75 metres long, and can only carry 14 people, or a payload of less than two tonnes. Zeppelin bombers in World War One were already more than twice as long, and carrying 16 tonnes!

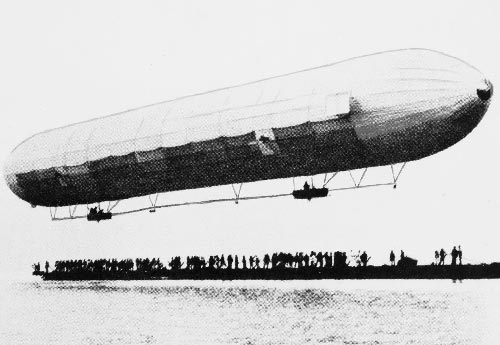

This, for example, is the LZ1, the very first of the Zeppelins. It was already 128 metres in length.

I, therefore, officially demand that we bring back the hydrogen-filled zeppelin!

They'd be very safe, especially with modern technology; giant bags full of hydrogen need be no more dangerous than giant fuel tanks full of kerosene, which I remind you are usually mere feet away from the jet engines that're burning the fuel. Modern control systems could intelligently manage multiply-compartmented cellular gas-bags, to automatically keep the zeppelin in the correct attitude, manage altitude, and keep the thing flying even if someone flies his Learjet straight into the side of the airship.

If people just can't get past their irrational terror of hydrogen, then you could of course just fill your zeppelin with helium, like the old American ships. But hydrogen gives more lift and can be easily manufactured from water; the world's helium supply all comes from natural gas. Lots of scientists and engineers are beavering away at finding efficient hydrogen-storage technology, too, because we'll need such technology for fuel-cell cars to become practical. I wouldn't be at all surprised if some of the same tech came in handy for managing lifting hydrogen in airships. And, heck, some of the hydrogen could also be used as fuel!

The one great advantage of a dirigible airliner is that legroom is not an issue. You don't get vast lifting power - even the gigantic, 245-metre-long Hindenburg only had a payload capacity around the same as that of a 70.6-metre-long 747-400 freighter - but you can have as much space as you like. You just don't get to fill that space with heavy stuff. Modern lightweight composite materials would be very helpful, here; we could probably make a 75-kilo grand piano if we wanted to, these days.

(One of the indications that the huge design-concept "Strato Cruiser lifestyle zeppelin" I linked to above is not a workable device is its hilarious inclusion of a topside swimming pool. That would weigh at least a hundred tonnes, and maybe a lot more; a standard Olympic pool contains at least 2,500 tonnes of water. It'd get a lot lighter when the airship turned and the water all sloshed out, of course.)

This, for instance, was just the dining room on the Hindenburg. It also had a lounge, a writing room, a smoking room (which contained the single lighter permitted aboard the vessel...), bathrooms, a crew mess hall, and small, but private, cabins for the 50-to-72 passengers.

"Oh, but what if someone tried to hijack the zeppelin, or blow it up?", I hear, from the people who don't mind having their shoes examined before they're allowed onto a plane.

Well, if the hijackers are only armed with box cutters, passengers could just run away from them through the modern zeppelin's acres of lounges, bars and tennis courts. And if terrorists had, let's say, a two-part shaped-charge-plus-thermite guaranteed-747-killer of a bomb, you could stand back and let 'em set it off, straight out into a gas-bag. The venting gas might catch fire, but the straight hydrogen inside the gas cell cannot support combustion by itself, and automated systems could dump the cell's contents out the side of the airship, or pump it into other cells. The damage would be a reduction of total lift by a few per cent, at worst. The frame of the airship could be a tensegrity structure of light composite beams and pressurised gas cells, so there'd be no single component an attacker could break to bring the whole ship down.

Even if the terrorists were running around with satchels full of bombs setting them off wherever they could, they'd still only be able to damage the gas cells adjacent to the passenger areas. You wouldn't even need to have gas cells in such locations, if you didn't mind making the airship somewhat larger.

Let's see - what other objections might there be?

Oh, yes: "What if a storm catches you? You'd be blown around like a toy balloon! Storms were a big problem for the old hydrogen airships, you know!"

Well, yes, they were. But that was because the old passenger dirigibles - and the early military ones - had a cruising altitude that seldom exceeded 2000 feet, and was often much lower. Like other aircraft of the time, they didn't have pressurised passenger compartments, so they simply couldn't fly too high without everyone needing oxygen masks and eight layers of sealskin.

Back in WWI some bomber airships were made as "height climbers", flimsier in structure to make them able to attain great altitude; doing so was rather dangerous, and horrible for the crew, especially when the engines started freezing up. Even when flying at modest altitude, the old dirigible engines often needed in-flight maintenance, which was a very exciting task. None of these problems would apply to a modern zeppelin, with a pressurised cabin and reliable engines, or even fuel-cell-powered electric motors.

With modern technology to manage the gas bags, modern engines, vectored thrust for much better maneuverability and pressurised gondolas, modern dirigibles would only need to worry about weather during takeoff and landing - and they could probably delay landing a lot longer than a 747 can. The rest of the time, they'd deal with storms in the same way that regular airliners do - by flying over them.

This does creates obvious limits to the routes airships could fly, though, since they couldn't make much headway against fast high-altitude air currents. We could easily make dirigibles twice as fast as the Zeppelins were, but that still only gets you to 260km/h. If you're happy to go in the same direction as a jet stream, though, it'll boost your speed by an easy 50-to-100 knots.

I think the main actual reason why nobody's brought back the zeppelin is that they wouldn't be cost-competitive with heavier-than-air craft, in the same way that ocean liners couldn't compete with planes. Airships might be able to compete for some exotic cargo applications, perhaps, as per the above-linked SkyHook JHL-40, a hybrid zeppelin/rotorcraft, but they certainly couldn't deliver passengers from A to B anything like as cheaply as an airliner.

In a fantasy world where everybody wasn't utterly determined to turn every field of human experience into a money-making operation, however (hey, how's that all working out for you, world?), and assuming that we actually could make 38,000-foot-capable pressurised zeppelins if we wanted to ("...we can put a man on the moon, but we can't..."), then airships certainly would be competitive, if one's aim was to travel in a pleasant way.

Ocean liners of the sky, able to cover 5000 kilometres a day and take off and land virtually anywhere, which cause people to actively compete to buy a house near the airport, just to be able to watch them. Sounds like an improvement to me.